Introduction

How are we to think of the complex numbers? What I mean is, with what fundamental structure at bottom do we take the complex numbers to be endowed? In short, what is the essential structure of the complex numbers? They form the complex field, of course, with the corresponding algebraic structure, but do we think of the complex numbers necessarily also with their smooth topological structure? Is the real field necessarily distinguished as a fixed particular subfield of the complex numbers? Do we understand the complex numbers necessarily to come with their rigid coordinate structure of real and imaginary parts?

These different perspectives ultimately amount, I argue, to mathematically inequivalent structural conceptions of the complex numbers, conceptions exhibiting different symmetries and thus also different automorphism groups. The additional structural features of the richer conceptions, after all, with the topology, the particular copy of ℝ as a distinguished subfield, or with the coordinate structure, are not determined uniquely by the algebraic field structure alone, and the coordinate structure is not determined uniquely by the topology. The automorphism groups of the conceptions are vastly different—the complex field admits crazy wild automorphisms, while the complex field over ℝ has only complex conjugation as a nontrivial automorphism, and the complex plane is rigid, having no nontrivial automorphisms at all. Which of these mathematical structural conceptions do we regard ultimately as the essential structure of the complex numbers? Indeed is there any one such essential structure?

It turns out that mathematicians do not agree—they do not all have the same conception of the complex numbers. Discussing the issue in various mathematical venues, I found a range of views, split roughly equally amongst the perspectives I discuss in this paper. I should like to discuss these various conceptions and then explain how they engage with several aspects of the philosophy of structuralism in the philosophy of mathematics.

Different perspectives on the complex numbers

To my way of thinking, there are at least four natural perspectives to take on the essential structure of the complex numbers, which I shall refer to under the following slogans.

-

Analytic: The complex field ℂ over ℝ

-

Smooth: The topological complex field

-

Rigid: The complex plane

-

Algebraic: The complex field

Two of these perspectives, it will turn out, arise from what amounts to the same underlying structural conception of the complex numbers (do you see which two?), and so those two perspectives are equivalent in this sense. Ultimately, therefore, we have here only three different perspectives in play. Let me elaborate on them.

Please enjoy this extended essay on the topic of the complex numbers. We shall see how our different various conceptions of them ultimately engage with several issues concerning the philosophy of structuralism in the philosophy of mathematics.

Toward the end of the essay we shall see how the complex numbers once made a key appearance in the midst of a contentious philosophical dispute, with many philosophers ultimately taking it decisively to refute what had seemed a promising position in the philosophy of mathematics.

The analytic conception

Many mathematicians like to consider the complex numbers ℂ as a field over ℝ, a view I refer to as the analytic conception, because it considers the structure of the complex field ℂ as it relates to and extends the real numbers ℝ, sitting with its analytic structure of the real line as a fixed distinguished subfield of ℂ. In particular, on the analytic view the complex field ℂ is conceived as the algebraic closure of ℝ—it is a degree-two extension of ℝ.

One common method to introduce the complex numbers as a field over ℝ is to introduce a symbol i for the imaginary unit and then present the complex numbers as formal sums a + bi with real numbers a, b ∈ ℝ. The sums obey the expected rules for addition and multiplication, subject to the rule i² = −1.

Since i² = −1, the complex field thus provides a system of numbers giving sense to expressions like √–1, while obeying the familiar algebraic rules of a field. One may easily observe in the complex numbers, however, that –i is also a square root of –1, because

\((–i)\cdot(–i)=(–1)^2\cdot i^2=i^2=-1.\)

Thus, both i and –i have the property of being square roots of –1, and indeed, these are the only square roots of –1 in the complex field.

A small conundrum may arise when one realizes that –i therefore also fulfills what might naively have been taken as the “defining” property of the imaginary unit i, namely, that it squares to –1. So this property doesn’t actually define i, in light of the fact that there is another distinct object –i that also has this property. Can we tell i and –i apart?

Not in the complex field, no, we cannot. The basic fact is that i and –i are indiscernible as complex numbers with respect to the algebraic structure of ℂ—any property that i has in the complex field ℂ over ℝ will also hold of –i. One way to see this is to observe that complex conjugation, the map

\(a + bi \ ⟼\ a – bi

\)

is an automorphism of the complex number field over ℝ, an isomorphism of the field structure with itself that fixes every real number. Since this automorphism swaps i with –i, it follows that any statement true of i in the complex numbers, expressible in the language of fields with a predicate for the real subfield ℝ, will also hold of –i. In short, they are indiscernible in ℂ over ℝ.

Thus, the analytic conception admits complex conjugation as a fundamental symmetry of ℂ over ℝ. Even though we have introduced i as a formal symbol, we do not consider the choice between i and –i as part of the underlying structure. To make this precise in the language of first-order logic, we might therefore present the analytic perspective of ℂ over ℝ as embodied by the structure ⟨ℂ, +, ·, 0, 1, ℝ⟩, where the language signature includes the field structure, as well as a predicate ℝ that explicitly picks out the intended copy of ℝ in ℂ. We do not have i available as a constant symbol or singular term in this language.

It is not difficult to see that conjugation is the only nontrivial automorphism of ℂ over ℝ, since if a field automorphism of ℂ fixes every real number, then it will be completely determined by whether it sends i to itself or to –i, meaning either that it is the identity automorphism or complex conjugation, respectively.

Another common way to present the complex field ℂ as a field over ℝ is as the quotient field ℝ[x]/(x² + 1), where we first form the polynomial ring ℝ[x], consisting of formal polynomial expressions in the indeterminate symbol x, and then take the quotient by the ideal generated by the irreducible polynomial x² + 1, thereby in effect treating this polynomial as 0, which means x² = −1. It follows that every polynomial in the quotient can be represented as a + bx, where a, b ∈ ℝ. And so ultimately this quotient construction amounts to the same as the a + bi conception.

With either presentation of ℂ over ℝ, one proceeds to prove the fundamental theorem of algebra, asserting that the resulting field ℂ is algebraically closed. And we may easily provide a categorical characterization of ℂ over ℝ, which determines it uniquely up to isomorphism, building on the categorical characterization of the real field up to isomorphism as the unique complete ordered field. Namely, the complex field ℂ is simply the algebraic closure of the real field ℝ, a degree-two extension of the complete ordered field ℝ, and any two such extensions are isomorphic by an isomorphism furthermore respecting the real numbers and hence respecting the “over ℝ” aspect of the characterization. Indeed, an alternative characterization of ℂ over ℝ is that ℂ is a nontrivial algebraic extension of ℝ—such an extension must have degree two, since the degree two extension is already algebraically closed.

At bottom the analytic conception of ℂ is that of an algebraically closed field with a single nontrivial automorphic symmetry, complex conjugation, whose fixed points constitute the distinguished real subfield.

The smooth conception

Many mathematicians prefer to emphasize what I call the smooth conception of the complex numbers, viewing the complex field as carrying also its familiar topological structure. On this account, ℂ is a certain topological field, a field that is also a topological space, in which addition and multiplication are continuous operations. With the familiar intended topology of the complex plane, we see easily that ℝ is the closure of the set ℚ of rational numbers. Since the rational numbers are inherent to the algebraic structure, it follows that in the topological complex field we can recover the real subfield ℝ as a distinguished subfield, the closure of ℚ. In this sense, the smooth conception of the complex numbers subsumes the analytic conception.

But in fact, I claim, the smooth conception and the analytic conception are equivalent—they arise from the same underlying structure. We have already seen how the topology reveals the distinguished copy of ℝ in ℂ as the closure of ℚ. Conversely, if we have fixed a copy of the real subfield ℝ in ℂ for the analytic conception, then even though we cannot distinguish i from –i, we can nevertheless still define the complex norm |z| of any complex number z, which is √(a² + b²), if z = a ± bi and a, b ∈ ℝ. The norm simply does not require us to have chosen between i and –i. Using the norm, we can then define the distance between any two complex numbers, and so we can realize the topology by viewing ℂ as a metric space. In short, identifying the real subfield enables us to specify the unique intended topology and vice versa, and so the analytic conception and the smooth conception of the complex numbers amount to having the same underlying structure for the complex field.

When considering automorphisms of the complex numbers under the smooth conception, we should of course require that they also respect the topology. But since any continuous automorphism of ℂ must fix every real number, since it must fix the rational numbers, it follows that the only continuous automorphisms of ℂ are the identity automorphism and complex conjugation, which are indeed homeomorphisms of the topology.

The rigid conception

Another common conception of the complex numbers is what I call the rigid conception, which incorporates into the field structure also the full coordinate structure of the complex plane. One elementary approach to this conception of ℂ is simply to identify complex numbers with points (a, b) in the plane ℝ × ℝ and define the algebraic operations by reference to the coordinates, like this:

\((a,b)+(c,d)=(a+c,b+d)\qquad (a,b)\cdot(c,d)=(ac-bd,ad+bc).\)

Such definitions were presented by Hamilton to the Royal Irish Academy in 1833, and are designed simply to implement the intended arithmetic of complex numbers, with

\((a+bi)+(c+di)=(a+c)+(b+d)i\)

and

\((a+bi)(c+di)=ac+adi+bci+bdi^2=(ac-bd)+(ad+bc)i.\)

With the structure of the complex plane, one can proceed furthermore to define the polar representation reiθ, with modulus r and argument θ, and one can translate back and forth definably between cartesian and polar coordinates.

In my experience, the complex plane construction is often successful for the pedagogical task of explaining how it could be that there is a field exhibiting the properties claimed of the complex numbers, how it could be, for example, that there is a number z with z² = −1. This amounts to the simple calculation with the number z = (0, 1), of course, following the rule we gave above, since

\((0,1)\cdot(0,1)=(0\cdot0-1\cdot 1,0\cdot 1+1\cdot 0)=(-1,0),\)

and the point (1, 0) is the multiplicative unit, so this is −1 as a complex number. For many mathematical beginners, it is the complex plane construction that de-mystifies the complex numbers.

The ordered-pair account of the complex field, if one regards the pair information as part of the underlying structure, amounts to viewing the complex field together with the real and imaginary part operators, defined by

\(\text{Re}(a+bi)=a\qquad \text{Im}(a+bi)=b.\)

So we are considering the complex numbers in effect as the structure ⟨ℂ,+,·,0,1,Re,Im⟩ with the two additional operators.

The coordinate structure carries more information than just the algebraic structure of the complex field, of course, for we can define the intended copy of ℝ in ℂ as those numbers whose imaginary part is zero. From the real field we can define the norm and hence also the topology, as we explained earlier. And we can naturally distinguish i from –i in the coordinate conception, since i has imaginary part 1, while –i has imaginary part −1. So in this conception we block the symmetry between i and –i. Indeed, in this conception the complex plane is rigid—it has no nontrivial automorphisms at all.

An equivalent presentation of the rigid conception of the complex plane arises from the a + bi presentation of ℂ over ℝ, but where we now fix the imaginary unit i as part of the structure ⟨ℂ, +, ·, 0, 1, i, ℝ⟩. In this language we can define the real and imaginary parts of any complex number. Indeed, to my way of thinking, the complex plane understanding of the a + bi presentation of ℂ is a more direct reading of that construction, since we take the imaginary constant i at face value as a distinguished constant, having made a particular choice of orientation, thus blocking the symmetry between i and –i.

The algebraic conception

Finally, many mathematicians find it natural to regard the complex numbers at bottom as a field, that is, endowed with its field operations as the (only) essential structure. This is a purely algebraic conception of the complex numbers, in which they are endowed with the algebraic operations of addition and multiplication to form the familiar complex field ⟨ℂ, +, ·, 0, 1⟩.

Indeed the complex field admits a categorical characterization in terms of this algebraic structure, a characterization determining it uniquely up to isomorphism. Namely, the complex field is, up to isomorphism, the unique algebraically closed field of characteristic zero and size continuum. Any two algebraically closed fields of characteristic zero (which just means that 1 + 1 + ⋯ + 1 is never 0) and size continuum are isomorphic. Equivalently, the complex field arises as the unique algebraically closed field of transcendence degree continuum over the rational field ℚ.

In fact, the first-order theory of algebraically closed fields of characteristic zero, a theory commonly denoted ACF₀ by the model theorists, is categorical in every uncountable power, which is the technical term expressing the fact that for every uncountable cardinality κ, there is up to isomorphism a unique such field of size κ. (An analogous result holds for ACFₚ in any prime characteristic p.) The reason is that the isomorphism type of an algebraically closed field of characteristic zero is determined by its transcendence degree over the prime subfield ℚ. The theory is not categorical for countable models, since we can form algebraically closed fields exhibiting any desired finite transcendence degree over ℚ, as well as the countably infinite transcendence degree, and these fields are nonisomorphic distinct countable models of the theory. But in the uncountable case, the transcendence degree will have to be the same as the size of the field itself, and thus we get the categoricity result. In this way, the complex numbers are characterized as the unique algebraically closed field of characteristic zero and size continuum.

Summary of the conceptions

So we have in the end three distinct conceptions of the complex numbers. First, the analytic account, for which we regard ℂ as a field extension of ℝ, specifically, the degree-two algebraic extension of ℝ, which is also the algebraic closure of ℝ, and which admits complex conjugation as the only nontrivial automorphism. That view, it turns out, is structurally equivalent to the smooth account, which endows the complex field ℂ with its familiar topology, since from the topology we can define the intended real subfield ℝ as the closure of the rationals, and conversely from ℝ we can define the topology. Next, we have the rigid account of the complex plane, which gives ℂ its coordinate structure of the real and imaginary parts, and which admits no nontrivial automorphisms. Finally, there is the algebraic conception of the complex field, with a rich, chaotic automorphism group that includes many wild automorphisms. The various conceptions are thereby distinguished from one another by their account of the extent to which the complex numbers exhibit a self-symmetric nature.

Google AI and ChatGPT weigh in

I was astounded to see that the Google AI overview in effect takes a stand amongst three conceptions of the complex numbers we have been discussing. Namely, while I was searching for references online, this is what it had told me:

ChatGPT takes the same stand.

The assertions made by these AI summaries are not mathematically correct, of course, since we have already discussed that the complex field admits innumerable wild automorphisms, not just the two continuous automorphisms. There are

many automorphisms of the complex field ℂ when it is considered with only its algebraic structure.

Nevertheless, perhaps it would be a charitable reading of the AI position to regard them as considering only automorphisms of ℂ over ℝ, that is, automorphisms fixing the real subfield, and this is the same as considering only continuous automorphisms. In this case, as we mentioned, there are only the two automorphisms of the identity and complex conjugation. On this charitable reading, therefore, the AI systems seem to be adopting the analytic/smooth conception of the complex numbers.

Nevertheless, they have not done so properly, since they do both refer to automorphisms of the complex field, rather than automorphisms of the complex field over ℝ. For this reason, in my view their precise claims are not ultimately correct mathematically, and this is a matter that would seem to require attention from the AI overseers.

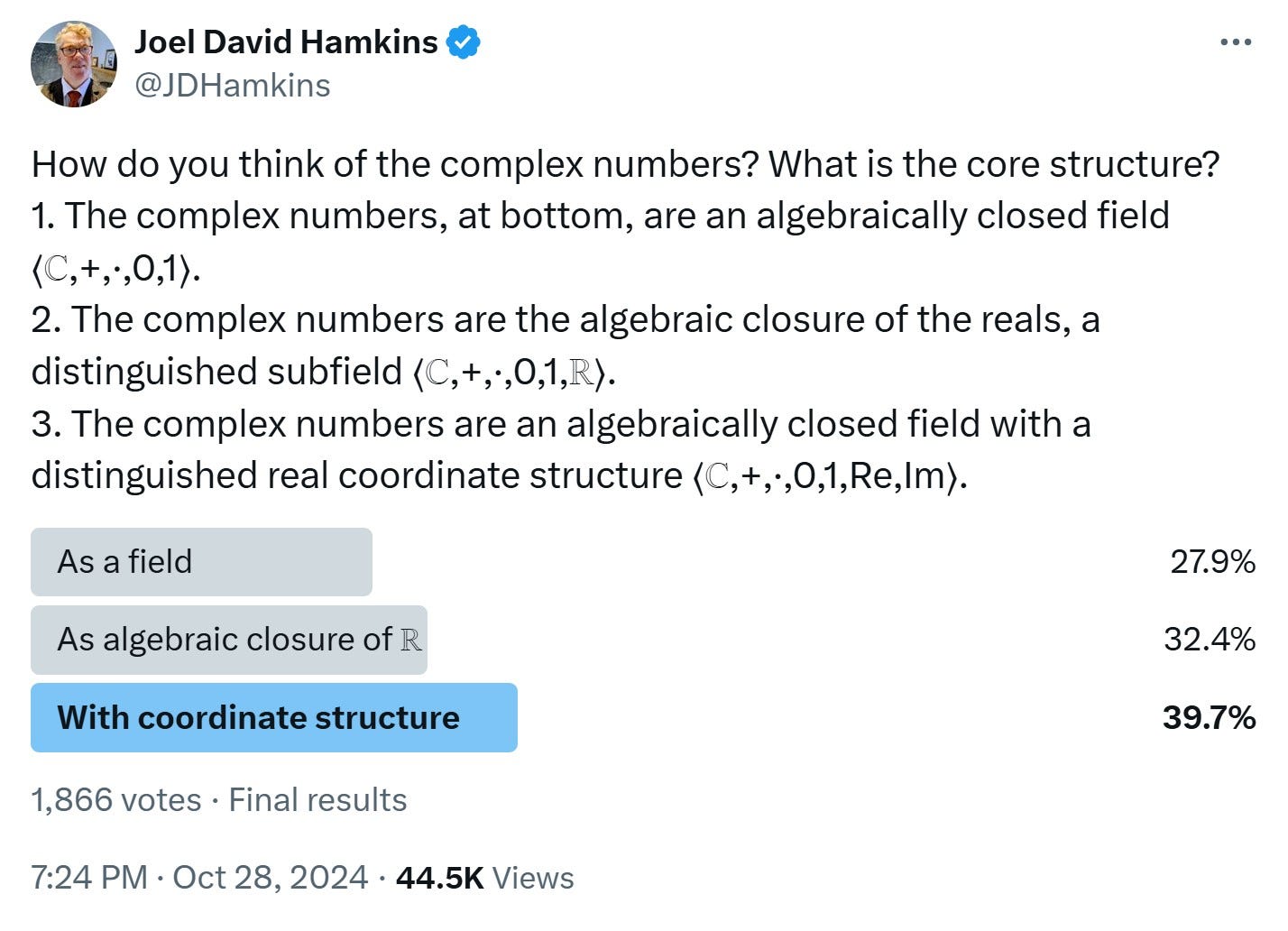

Strongly held mathematical views

I ran an unscientific poll on Twitter that revealed a dispersed range of views in the mathematical/philosophical community for how to conceive of the complex numbers.

And yet, despite the variation in views, many mathematicians are quite passionate about their favored answer, viewing those with the opposing view as making a fundamental mistake.

For example, one respondent expressed the view that the algebraic conception is “definitely wrong,” and another user says, “the coordinate view of [the complex plane] is what lives in my spine.” Mathematician Daniel Litt (algebraic geometry, number theory) mentions that the complex plane conception “is tantamount to choosing a square root of −1, I guess, which I think of as immoral.” He adds that “At the very least making such a choice often leads to confusion later on.” Mathematician Barbara Fantechi (algebraic geometry) states, “I was taught that choosing a square root of (−1) is wrong.” The view is that somehow it is a kind of mathematical sin to break the symmetry between i and −i in ℂ over ℝ and thus wrong to adopt the rigid perspective of the complex plane conception of ℂ. Nevertheless, mathematician Rogier Brussee responds that, “Immoral sure, but, well, you know, the snake and the apple things; it can be a bloody convenient immorality at times.” Mathematician David Madore writes:

People who study algebraic stacks and such questions are always careful to speak of “an” algebraic closure of a field (or even “a” field with 8 elements) because they are unique up to isomorphism but the isomorphism is non-unique. BUT even these people say “the” field of complex numbers, never “a” field of complex numbers, which suggests that they rigidify ℂ so as not to have any automorphism, so probably as per the complex plane conception in your poll.

So mathematicians hold different conceptions of the complex numbers, and many of them even look upon the alternative conceptions as fundamentally wrong or misguided.

Interpreting ℝ in the complex field ℂ

We have seen that the real field ℝ is not definable in the complex field ℂ if one has only the algebraic field structure of ℂ, as with the algebraic conception. I should like to observe, further, that we cannot even interpret ℝ in the field ℂ. To interpret ℝ in ℂ is a much weaker way of finding a copy of ℝ in ℂ, after all, where we find it not necessarily as a subfield, but rather as a definable structure built using whatever algebraic resources are available in ℂ.

What does it mean exactly to interpret one mathematical structure in another? This is a technical term used in model theory and mathematical logic to refer to the situation when one can provide a definable copy of the first structure in the second, by specifying a definable domain of k-tuples (not necessarily just a domain of individuals) and definable interpretations of the atomic operations and relations, as well as a definable equivalence relation, a congruence with respect to the operations and relations, such that the first structure is isomorphic to the quotient of this definable structure by that equivalence relation. All these definitions should be expressible in the language of the host structure. One may proceed recursively to translate any assertion in the language of the interpreted structure into the language of the host structure, thereby enabling a complete discussion of the first structure purely in the language of the second.

For example, we can define a copy of the integer ring ⟨ℤ, +, ·⟩ inside the semi-ring of natural numbers ⟨ℕ, +, ·⟩ by considering every integer as the equivalence class of a pair of natural numbers (n, m) under the same-difference relation, by which

\((n,m)\equiv(u,v)\ \iff\ n-m=u-v\ \iff\ n+v=u+m.\)

Integer addition and multiplication can be defined on these pairs, well-defined with respect to same difference, and so we have interpreted the integers in the natural numbers. Similarly, the rational field ℚ can be interpreted in the integers as the quotient field, whose elements can be thought of as integer pairs (p, q) written more conveniently as fractions p/q, where q ≠ 0, considered under the same-ratio relation

\(\frac pq\equiv\frac rs\qquad\iff\qquad ps=rq.\)

The field structure is now easy to define on these pairs by the familiar fractional arithmetic, which is well-defined with respect to that equivalence. Thus, we have provided a definable copy of the rational numbers inside the integers, an interpretation of ℚ in ℤ.

We can also similarly interpret the complex field ℂ in the real field ℝ by considering the complex number a + bi as represented by the real number pair (a,b) as in the rigid conception of ℂ we discussed above. By keeping only the field structure on these pairs, we have an interpretation of the complex field in ℝ, but we can also interpret the structures corresponding to the analytic/smooth and rigid conceptions of ℂ as well.

Meanwhile, what I claim is that it is not possible conversely to interpret the real field ℝ inside the complex field ℂ with only its algebraic structure. The proof of this is grounded in the fact that the complex field admits only countably many different types of elements up to automorphism, even with respect to finitely many parameters p. Namely, either an element is algebraic over ℚ(p), in which case it is determined up to automorphism by its minimal polynomial, or it is transcendental over ℚ(p), and all transcendental elements are automorphic by an automorphism fixing the parameters. By applying this idea successively, it follows also that there are only countably many types of k-tuples of elements of ℂ. That is, if two k-tuples a and b from ℂ obey the same minimal-polynomial algebraic relations in ℂ over ℚ(p), then there is an automorphism of ℂ moving a to b and fixing p. In short, the complex field ℂ with only the algebraic structure makes distinctions amongst only countably many types of k-tuples with respect to expressible properties.

This is enough to see that we cannot interpret ℝ, since any copy of ℝ will exhibit its corresponding rational numbers that arise within it, and these numbers admit uncountably many cuts as realized by points in the interpreted copy of ℝ. But the problem is that these cuts thereby realize different, discernible types of elements in the interpreted copy of ℝ, which are therefore discernible in the host structure ℂ. In short, any interpreted copy of ℝ will require us to have distinguished uncountably many different kinds of k-tuples, but we have said this is impossible in the complex field. So there is no interpretation of ℝ in ℂ.

Set-theoretic indiscernibility of i and –i

The analytic/smooth conception of the complex field ℂ over ℝ highlights the fundamental symmetry between the imaginary unit i and its negation –i. It is not possible to distinguish these two complex numbers by any property expressible in the complex field, even when we have fixed the canonical subfield of the real subfield ℝ in ℂ, because complex conjugation swaps these two elements, while preserving all the expressible properties of ℂ as a field extension of ℝ.

A few years ago (Hamkins 2022), I realized that it is relatively consistent with ZFC that we can definably construct a copy of the complex numbers ℂ over ℝ in such a way that i and –i are not only indiscernible in the field structure of this copy of ℂ, but also the particular set-theoretic objects i and –i that are used in this structure are indiscernible in the larger set-theoretic background in which the construction is undertaken.

Goal. A definable copy of the complex field in which the two square roots of −1 are indiscernible not only in the field structure but also in the set-theoretic background in which the construction of the field takes place.

These two aims are in tension, for we want the particular copy of ℂ to be set-theoretically definable (defined with respect to the set-theoretic background as a particular set-theoretic object, not just defined up to isomorphism), but the individual square roots of −1 are to be set-theoretically indiscernible.

The goal is not always possible in ZFC. For example, some models of ZFC are pointwise definable, meaning that every individual set is definable in them by some distinguishing set-theoretic property—see further discussion in (Hamkins, Linetsky, Reitz 2013). More generally, if the V = HOD axiom holds, then there is a definable global well-order of the set-theoretic universe, and with any such order we could define a linear order on {i, –i} in any definable copy of ℂ, which would allow us to define each of the roots. For these reasons, in some models of ZFC, it is not possible to achieve the goal, and the most we can hope for is a consistency result.

But indeed, the goal is achievable, as I shall now explain.

Theorem. If ZFC is consistent, then there is a model of ZFC that has a definable complete ordered field ℝ with a definable algebraic closure ℂ, such that the two square roots of −1 in ℂ are set-theoretically indiscernible, even with ordinal parameters.

Proof. The proof makes use of what are known as Groszek-Laver pairs, definable pair sets having no ordinal-definable element. See (Groszek, Laver 1987) for a very general version of this. The result also appears as theorem 4.6 in my 2018 paper with Gunter Fuchs and Victoria Gitman. The arguments provide a model of set theory with a definable pair set A = {i, j}, such that neither element i nor j is definable from ordinal parameters. The pair set is definable, but neither element is definable.

To undertake the construction, we start with one of the standard definable constructions of the real field ℝ. For example, we could use Dedekind cuts in ℚ, where ℚ is constructed explicitly as the quotient field of the integer ring ℤ in some canonical definable manner, and where the integers are definably constructed from a definable copy of the natural numbers ℕ, such as the finite von Neumann ordinals. So we have a set-theoretically definable complete ordered field, the real field ℝ.

Given this and the set A = {i, j}, we follow a suggestion of Timothy Gowers in the discussion of this problem on Twitter. Namely, we use the elements of A as variables to form the polynomial ring ℝ[A], meaning ℝ[i, j], where i and j are the two elements of A. It is not necessary to distinguish the elements of A to form this ring of polynomials, since we take all finite polynomial expressions using real coefficients and elements of A raised to a power. (In particular, although I have referred to the elements as i and j, there is to be no suggestion that I am somehow saying i is the “real” i; I am not, for I could have called them j, i or j, k or a, a′, and so on.) Then we quotient by the ideal (i² + 1, j² + 1, i + j), which is defined symmetrically in the elements of A. Let ℂ be the quotient ℝ[i, j]/(i² + 1, j² + 1, i + j), which will make i and j the two square roots of −1, and so by the fundamental theorem of algebra this is a copy of the complex numbers.

Since ℝ and A were definable, and we didn’t need ever to choose a particular element of A in the construction to define the polynomial ring or the ideal, this copy of ℂ is definable without parameters. But since i and j are set-theoretically indiscernible in the model of set theory in which we are undertaking the construction, it follows that their equivalence classes in the quotient are also indiscernible. And so we have a definable copy of the complex field ℂ, extending a definable copy of ℝ, in which the two square roots of −1 are indiscernible not just in the field structure, but fully in the set-theoretic background in which the fields were constructed. □

In particular, in this model of set theory, there will be absolutely no way to distinguish the two roots by any further definable structure, whether using second-order or higher-order definitions of the field ℂ or using any definable set-theoretic property whatsoever. (However, we clearly can distinguish them if we allow parameters, since we can just choose one of them and use it to define the rigid complex plane.)

The analysis suggests a natural further inquiry. Namely,

Question. Is there a model of set theory with a definable copy of the complex field ℂ, such that the hierarchy of relative definability and indiscernibility in ℂ matches the set-theoretic relative definability and indiscernibility of the objects?

That is, we would want to mimic the phenomenon of i and –i in the above construction with all complex numbers, so that √2 and −√2 were also indiscernible, not just in this copy of ℂ but also in the set-theoretic background, and the 4th roots of 2 would be set-theoretically indiscernible, but each can set-theoretically define both √2 and −√2. In other words, I would want the set-theoretic definability hierarchy to match the complex-number-theoretic definability hierarchy.

This question remains open, although I believe that perhaps it might be answerable via iterated Sacks forcing in a manner similar to that used in many papers by Marcia Groszek, and in particular, in my 2019 paper with her, The Implicitly constructible universe.

The complex field as a problem for singular terms

I should like briefly to relate the story of how the complex field ℂ came to play a decisive role in a certain philosophical dispute in the philosophy of mathematics—many philosophers took it ultimately to refute a certain otherwise tempting position regarding the philosophy of structuralism.

To be sure, one finds diverse and often incompatible accounts of structuralism in the philosophy of mathematics, for we have abstract structuralism, ante-rem structuralism, eliminative structuralism, in-re structuralism, post-rem structuralism, modal structuralism, structuralism in mathematical practice, the structuralist imperative, and more—see my overview in (Hamkins 2021, p.27-36).

I have emphasized what I see as two parallel threads of structuralism, developing largely independently in mathematics and philosophy. Namely, the philosophical treatment of structuralism is often seen as growing out of Benacerraf’s influential work (1965, 1973), and it is concerned with core philosophical issues, such as the ontology of mathematics and the problem of reference to abstract mathematical objects. Meanwhile, structuralism in mathematics, as I see it, grows mainly out of the much-earlier categoricity results of Dedekind and others in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, leading to the idea currently pervasive in mathematical practice that a mathematician rightly considers mathematical objects only up to isomorphism—this is perhaps the single most widely held philosophical position in mathematics held by mathematicians. The philosophical treatment of structuralism, by my lights, has often been little connected with actual mathematics, and likewise mathematicians talking even at length about structuralism rarely mention Benacerraf or the other philosophical literature on structuralism. In my experience, the two threads of structuralism are thus often focused on fundamentally different matters. However, the situation is improving in recent years.

On the mathematical side of structuralism, I state the structuralist imperative as follows:

The structuralist imperative. For mathematical insight, investigate mathematical structure, the relations among entities in a mathematical system, and consider mathematical concepts only as being invariant under isomorphism. Therefore, do not concern yourself with the substance of individual mathematical objects, for this is mathematically fruitless as structure arises with any kind of object. (Hamkins 2021)

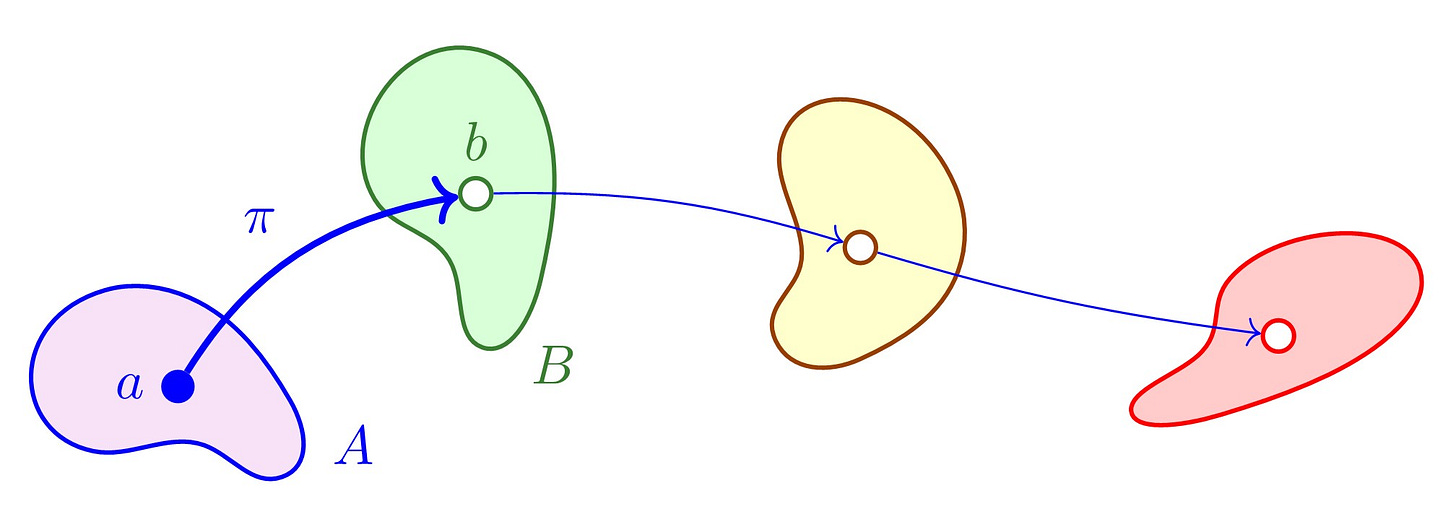

We might say that an object a in structure A plays the same structural role as object b in structure B exactly when there is an isomorphism of A with B carrying a to b.

It seems natural to consider the isomorphism orbit of an object in a structure, the equivalence class of the object/structure pair (a, A) with respect to the same-structural-role-as relation.

\((a,A)\equiv(b,B)

\qquad\iff\qquad\exists\,\pi:A\cong B\quad \pi(a)=b.\)

This orbit tracks how a is copied to all its various isomorphic images in all the various structures isomorphic to A. And whether or not these objects are definable or discernible in their structures, it is precisely the objects appearing in the isomorphism orbit that play the same structural role in those structures that a plays in A.

Meanwhile, according to Shapiro (1996, 1997), the slogan of structuralism is that “mathematics is the science of structure.” This view leads ultimately to the position of ante-rem or abstract structuralism, the view that what mathematical objects are, at bottom, is the structural roles that those objects play in a mathematical system. Thus, what the real number 1 is, at bottom, is the structural role of being the multiplicative identity. What the number √2 is, is the structural role played by a number that is positive and whose square is 1 + 1, where 1 is the multiplicative identity. And so forth.

The position may be initially attractive. But I have criticized it on the grounds that it is ultimately anti-structuralist. Yes, I argue that abstract structuralism is anti-structuralist. The reason is that it is preoccupied with answering the question of what the mathematical objects really are at bottom. But the structuralist imperative implores us specifically against that—it is not a structuralist undertaking. According to the structuralist imperative, to try to find out what mathematical objects really are is an anti-structuralist endeavor, a fruitless quest, as well as mathematically irrelevant. It just doesn’t matter what the objects really are, as structure can arise with any kind of object, and so it is anti-structuralist to provide an answer, even if the answer that is provided is that the objects are at bottom purely structural. (Hamkins 2021, p. 35-36)

And now let us observe how the complex field made its entrance into the philosophical dispute (see Shapiro 2012). The main observation to make is that the structural role played by i in the complex field ℂ is identical to the structural role played by –i in ℂ, precisely because complex conjugation is an automorphism that swaps them. In short, the numbers are distinct, but the role played by them in the relevant structure ℂ is exactly the same. So we cannot coherently identify the mathematical objects with the structural role that they play in a mathematical system, because i and –i play exactly the same role in the complex field ℂ, and yet they are not the same object. Isn’t this a clear refutation of that philosophical position?

Furthermore, there was nothing special about i and –i in the argument, since if we are considering ℂ under the algebraic conception, then every single irrational complex number admits distinct automorphic images. The number √2 plays the same role in the complex field ℂ as does −√2, and e and π play the same role, and so forth. We have mentioned that indeed there are only countably many structural roles played by numbers in ℂ, since there are the roles played by specific algebraic numbers, while all transcendental numbers are automorphic with each other. But there are uncountably many complex numbers.

The problem of nonrigid structuralist existence

Let me conclude this essay by turning to another related philosophical problem concerning the complex field and the philosophy of structuralism.

In my view, in light of the categoricity results characterizing all our familiar mathematical structures, the structuralist practice is what enables a direct structuralist reference to abstract mathematical objects. Namely, in structuralist mathematics, when referring to the real field ℝ, we don’t point at a particular field, kept like the iron rod in a cabinet in Paris, to serve as the canonical instance of this structure. Rather, we simply say, “take any complete ordered field.” Since we only care about ℝ up to isomorphism and any such field is isomorphic to any other, any such field will serve in our argument. Our structuralist argument will not depend on the underlying substance out of which that field had been formed. In this way, the structuralist practice in mathematics relies on our having categorical characterizations for all our core mathematical structures in the first place, since the categorical characterizations are what enable the direct structuralist reference to them.

In regard to the complex numbers, since we have categorical characterizations of the complex field ℂ under each of the several conceptions—the analytic/smooth conception, the rigid conception, and the algebraic conception—we can thus make direct structuralist reference to the complex numbers under any of the three conceptions, whichever is desired.

But now a certain problem arises. Suppose we want to make structuralist reference to the complex field under the analytic conception, say, as the field ℂ over ℝ. The categorical characterization is that ℂ is the algebraic closure of ℝ, and so we make structuralist reference to it by saying, “take the algebraic closure ℂ of a complete ordered field ℝ.” That is fine.

But in order for this to work in mathematical proof, we must earlier have proved that indeed there is such a structure, that there is an algebraic closure of a complete ordered field. But now we come to the crux of the issue. Namely, all the constructions of ℂ over ℝ of which I am aware break the symmetry between i and –i during the course of the construction—the constructions themselves provide a way of choosing between i and –i at an early stage of the process, even if this extra structure is eventually omitted in the end.

Take the presentation of ℂ over ℝ using formal sums of the form a + bi, say, where i was introduced as a purely formal symbol. Obviously, this construction enables us to choose that this symbol represents i and not –i. We specifically had to forget this constant term in the final field in order to reintroduce the symmetry between i and –i.

Similarly, in the quotient construction ℝ[x]/(x² + 1), the polynomial construction itself obviously distinguishes x from –x and thus ultimately distinguishes i from –i. We cast that extra structure aside at the end by keeping only the field structure over ℝ and not the distinction between x and –x.

When we construct ℂ over ℝ from the complex plane, with the coordinate structure, it is just the same. We construct the rigid complex plane, but then keep only the real-part operator Re, while forgetting the imaginary part operator Im. Our field ℂ over ℝ arises from a process of forgetting from what was the rigid structure of the complex plane.

In every case, therefore, when proving that there is such a thing as the complex field ℂ over ℝ, what we actually do first is construct a rigid structure, in effect the complex plane, and then take a suitable reduct to forget some of the structure in order to admit the symmetry of complex conjugation.

Earlier I had quoted Daniel Litt, who described it as mathematically immoral to break the symmetry between i and –i. My problem with this is that I don’t know any construction of ℂ over ℝ that doesn’t break this symmetry during the course of the construction. In order to build such a field in the first place, we first build a rigid structure and then afterward drop the extra structure in order to recover the desired symmetry. Must we be immoral?

Indeed, I claim that this structure-forgetting step is inherent to the process, and I don’t believe we can provide (in ZFC set theory, say) a construction of the complex field ℂ over ℝ that does not during the course of the construction introduce a symmetry-breaking choice between i and –i. The final steps of the construction will invariably apply a forgetful operation to remove this extra structure and thereby reintroduce the desired symmetry.

I have argued that this phenomenon is inherent in mathematic practice, by which nonrigid structure invariably arises always as a reduct substructure of a previously constructed rigid structure. It is simply too difficult ever to specify or refer directly to a nonrigid structure, in which objects of the conception are indiscernible, without first being able to discern them in a richer structural context.

We don’t start with a naked copy of ℂ and then seek to impose an orientation on it that will enable us to resolve i from –i. Rather, we proceed oppositely: instances of mathematical structures are obtained from richer contexts where the objects were already individuated. We might build a copy of ℂ from ordered pairs of real numbers, for example, where we can discern (0,1) from (0,-1) and therefore i from –i in this particular copy of ℂ. Every particular copy of ℂ and indeed every particular mathematical structure of any kind arises similarly from a context in which the objects are individuated. (Hamkins 2021, p. 46-47)

And then I point out how this philosophical observation becomes a mathematical theorem in set-theoretic foundations.

When using ZFC set theory as a foundation of mathematics, this philosophical observation becomes a mathematical theorem: every set is a reduct substructure of a rigid structure, a structure in which every individual plays a distinct structural role. The reason is that every set is a subset of a transitive set, and every transitive set is rigid with respect to the ∈-membership relation. Indeed, the set-theoretic universe ⟨V,∈⟩ as a whole is rigid—any two objects in the set-theoretic universe are therefore distinguishable as sets and play different set-theoretic roles… Therefore, every mathematical structure that can be realized in set theory at all can be realized as a reduct substructure of a rigid structure. We can refer to distinct individuals in the original structure by the distinct structural roles they play in the larger context. (Hamkins 2021, p. 47)

The earlier results on set-theoretic indiscernibility, however, can be seen as pushing back against the inherency argument above, by showing that it is at least consistent with ZFC that one can definably undertake a construction of ℂ over ℝ without having any set-theoretically definable method of discerning i from –i. Nevertheless, although the sets used in the Groszek-Laver pair set {i, j} in that construction are set-theoretically indiscernible, they do play different structural roles in the set-theoretic universe, which is rigid, and so in this sense we can still view the polynomial ring ℝ[i,j] used in the construction as rigid.

Conclusion

I began with the question, how shall we view the complex numbers? With which fundamental structure is it to be endowed? Ultimately, my answer to this question is that the complex field exhibits all three of the structural conceptions I have discussed, each considered on its own for a purpose, and although these structures are different and inequivalent, it is wrong to insist on only one conception.

In particular, the rigid conception plays an important seminal role for the other conceptions of the complex field. Even though the rigid conception is rejected as misguided by many mathematicians, sometimes strongly so, nevertheless all the usual constructions of the structures instantiating the other conceptions have at their heart a rigid presentation of the complex plane, with the symmetries reintroduced only afterward by forgetting the extra structure used in the construction.

Paul Benacerraf. “What Numbers Could not Be”. The Philosophical Review 74.1 (1965), pp. 47–73. issn: 00318108, 15581470. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2183530.

Paul Benacerraf. “Mathematical Truth”. Journal of Philosophy 70 (1973), pp. 661–679.

Gunter Fuchs, Victoria Gitman, and Joel David Hamkins. “Ehrenfeucht’s Lemma in Set Theory”. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic 59.3 (2018), pp. 355–370. doi: 10.1215/00294527-2018-0007. arXiv:1501.01918.

Marcia J. Groszek and Joel David Hamkins. “The implicitly constructible universe”. Journal of Symbolic Logic 84.4 (2019), pp. 1403–1421. doi:10.1017/jsl.2018.57. arXiv:1702.07947.

M. Groszek and R. Laver. “Finite groups of OD-conjugates”. Period. Math. Hungar. 18.2 (1987), pp. 87–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01896284.

Joel David Hamkins. The real numbers are not interpretable in the complex field. Mathematics and Philosophy of the Infinite. 2020. http://jdh.hamkins.org/the-real-numbers-are-not-interpretable-in-the-complex-field/.

Joel David Hamkins. Lectures on the Philosophy of Mathematics. MIT Press, 2021. isbn: 9780262542234. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262542234/lectures-on-the-philosophy-of-mathematics/

Joel David Hamkins. A model of set theory with a definable copy of the complex field in which the two roots of −1 are set-theoretically indiscernible. Mathematics and Philosophy of the Infinite. 2022. https://jdh.hamkins.org/a-model-of-set-theory-with-a-definable-copy-of-the-complex-field-in-which-the-two-roots-of-1-are-set-theoretically-indiscernible/

Joel David Hamkins, David Linetsky, and Jonas Reitz. “Pointwise definable models of set theory”. Journal of Symbolic Logic 78.1 (2013), pp. 139–156. doi: 10.2178/jsl.7801090. arXiv:1105.4597.

Stewart Shapiro. “An “i” for an i: Singular Terms, Uniqueness, and Reference”. Review of Symbolic Logic 5.3 (2012), pp. 380–415.

Stewart Shapiro. “Mathematical Structuralism”. Philosophia Mathematica 4.2 (May 1996), pp. 81–82. issn: 1744-6406. doi: 10.1093/philmat/4.2.81.

Stewart Shapiro. Philosophy of Mathematics: Structure and Ontology. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Parts of this essay were adapted from my blog posts in 2020, 2022, as well as my book 2021.