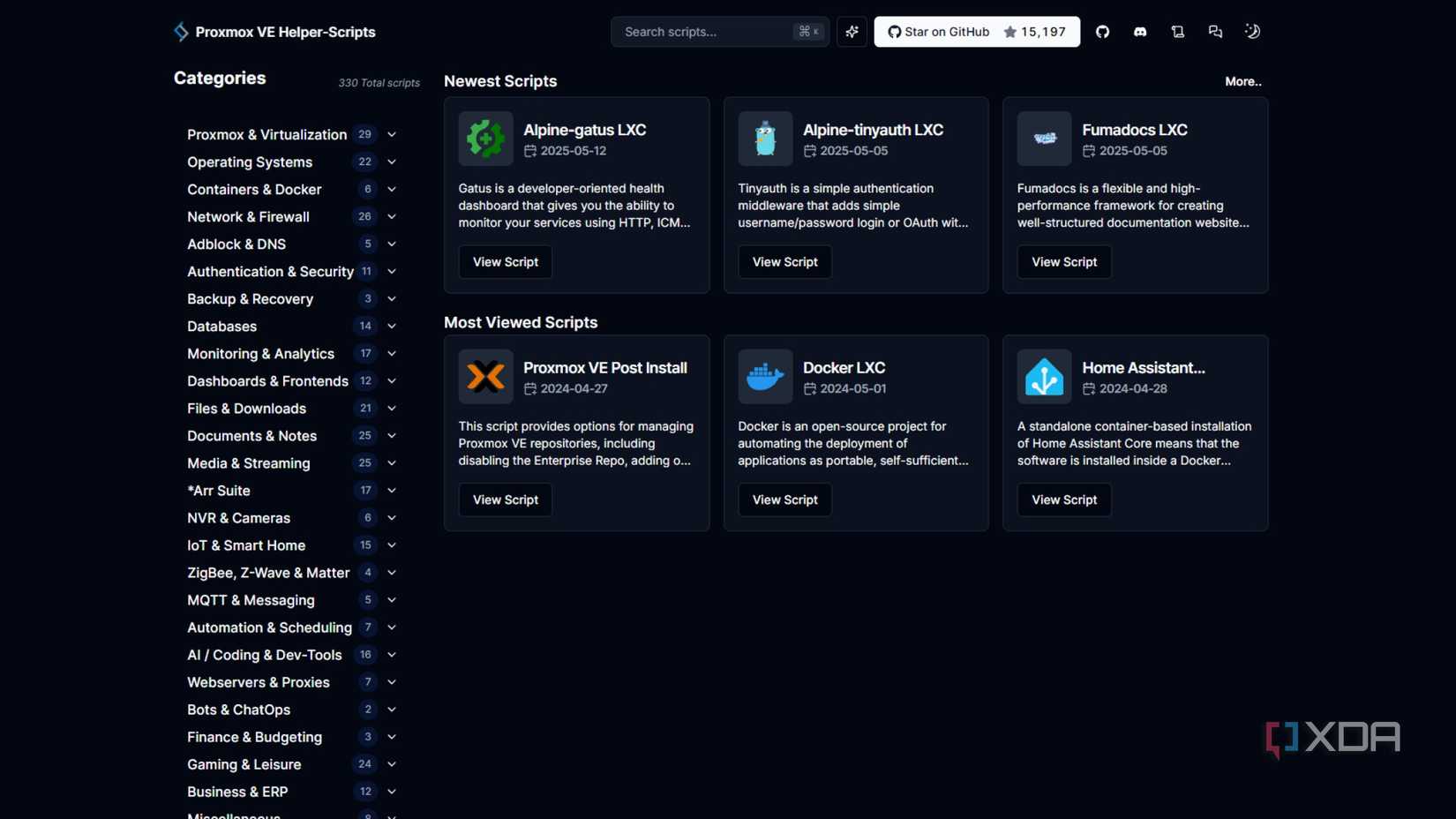

If you run a Proxmox server, you’ve almost certainly come across the Proxmox VE Helper Scripts. With over 400 scripts covering everything from Home Assistant to Plex to Ollama, they let you spin up fully configured LXC containers with a single command. They’re brilliant, and I use them regularly. But I would never, ever run one without reading it first, and neither should you.

These scripts run as root on your hypervisor. That’s the most privileged level of access in your entire home lab environment. If something goes wrong, whether through malice, negligence, or just an unaccounted-for edge case, you’re not losing a container… you’re potentially losing everything. We’ll go through an example script, learn how to read it, and what you can do to minimize the risk of running these scripts.

What actually happens when you run a Proxmox helper script

It’s more than just one script

First, we’ll break down one of the Proxmox Helper scripts, so you can understand what it is that you’re looking at. We’re going to look at the Ollama LXC creation script as It’s one of the more popular ones right now, for obvious reasons. The installer script is invoked by running the following in the host of your Proxmox machine:

bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/community-scripts/ProxmoxVE/main/ct/ollama.sh)"

That command downloads a script from GitHub and immediately pipes it into bash, without a pause, review process, or confirmation of what you’re about to execute. Here’s what that script actually contains, and you can follow along by going to the raw script on GitHub and viewing it yourself.

The ollama.sh file is deceptively simple. It declares a handful of variables: the application name, default CPU cores, RAM, disk size, base OS (Ubuntu 24.04), and some tags. Then it does something critical: it downloads and sources another script with the following command:

source ‹(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/community-scripts/ProxmoxVE/main/misc/build.func)

This is the part that obfuscates much of the process, but thankfully, this build.func script is reused across most of these scripts. Once you’ve understood it once, you know what most of the scripts do. Check in every now and again to ensure it hasn’t drastically changed, but aside from that, sanity checks are typically a lot quicker after you’ve understood this file.

That single line fetches “build.func” from GitHub and executes it in the current shell context, with full root privileges. After that, the script calls three functions provided by build.func: “start”, “build_container”, and “description”. That’s it. The CT script is essentially a config file that bootstraps a much larger machinery. The ollama.sh file does very little in comparison.

Breaking down build.func

The core of the Proxmox helper scripts

build.func is where things get interesting, and where the real complexity lives. It’s the backbone of the entire helper script ecosystem, and it does a lot:

- Initializes variables and defaults for whatever application you’re installing

- Presents interactive menus so you can choose OS versions, container types (privileged or unprivileged), passwords, and resource allocation

- Handles storage selection across your Proxmox storage pools

- Creates the actual LXC container by calling yet another remote script, “create_lxc.sh”

But build.func doesn’t stop at its own code. It sources additional dependencies:

- core.func for foundational utilities like color formatting, validation, and message output

- error_handler.func for structured error reporting

- api.func for diagnostics and reporting back to the project

Each of these is fetched from GitHub at runtime. Each executes with root privileges on your Proxmox host. Once the container is created, a separate install script runs inside it. For Ollama, that’s “install/ollama-install.sh”, which itself sources “misc/install.func”. That utility script handles network verification (checking connectivity to Google, Cloudflare, and Quad9 DNS), runs OS updates, configures SSH, sets up auto-login, and configures the MOTD.

When you run that single one-liner, here’s the chain of remote code execution that actually happens:

1. ct/ollama.sh is fetched and executed on your Proxmox host

2. misc/build.func is fetched and sourced

3. misc/core.func is fetched and sourced

4. misc/error_handler.func is fetched and sourced

5. misc/api.func is fetched and sourced

6. misc/tools.func is fetched and executed, and it’s the toolkit that powers package installation, version management, and deployment across all helper scripts

7. install/ollama-install.sh is fetched and executed inside the container

8. misc/install.func is fetched and sourced inside the container

That’s eight separate downloads of remote code, all triggered by a single command, all running with elevated privileges. If any one of those files were compromised at the source, whether through a malicious commit or a compromised GitHub account, the malicious code would execute with full root access on your hypervisor.

“But it’s open-source” I hear you say. Unfortunately, just because it’s open-source doesn’t mean it can’t do anything malicious. You can audit each of these files before running them, but will you? Often, people rely on others to do that and raise the alarm, and if the xz Utils fiasco taught us anything, the truth is that people often don’t.

Scripts can silently break

Especially when using specific hardware

Security isn’t the only reason to read these scripts before running them. Sometimes they just don’t account for your hardware.

The Ollama script defaults to Ubuntu 24.04 as its base OS. If you’re planning to use GPU passthrough for local LLM inference (which is the entire point of running Ollama on dedicated hardware), this can create a real problem for anyone running Nvidia Pascal-generation GPUs like the GTX 1080, 1070, or 1060.

The Ollama helper script installs Nvidia drivers as part of its GPU passthrough setup, but it doesn’t check which GPU generation you have. A user with a GTX 1080 could run the script, watch it complete successfully, and then discover their GPU simply doesn’t work inside the container. No error during installation, no warning, just a non-functional setup that you’d have to debug yourself. This is the kind of edge case that automated scripts inherently struggle with. Hardware compatibility is nuanced, and a one-size-fits-all approach to driver installation will always leave some users behind.

When Arch Linux rolled forward to newer Nvidia driver branches, many Pascal GPU owners suddenly found themselves with broken graphical environments. The Proxmox community scripts have the same blind spot. If you understand the scripts, you can modify them to suit your needs, but that requires reading through them and modifying them to fit your use case.

Scripts are sometimes removed, too

Some software is better left to the user to deploy

Sometimes a community script becomes so problematic that the maintainers have to remove it altogether. The Habitica script is a recent example. This pull request in the community-scripts repository addresses its removal, and the reasons highlight an inherent problem within the project.

Habitica, the gamified task management app, is a complex Node.js application with a sprawling dependency tree. The community script to deploy it in an LXC container started experiencing installation failures when the “stylus-0.54.5” dependency began returning 404 errors. On top of that, there were security warnings about deprecated dependencies like Chokidar 2, which hasn’t received security updates since 2019.

Problems like these aren’t unique to Habitica. The Authentik authentication script was also removed after recurring issues made it unmaintainable. The maintainers noted they’d reconsider if Authentik provided a cleaner packaging method, like a .deb package or prebuilt binary.

However, there’s a clear pattern here. Complex applications with deep dependency trees are fragile when wrapped in automated installation scripts, and when upstream dependencies break or are abandoned, the community script breaks too, leaving users with broken installations and no clear fix. These scripts promise easy-to-use simplicity, but that simplicity depends on the stability of sometimes dozens of upstream projects that the script maintainers have zero control over.

xz Utils and the trust paradigm of open source projects

Who’s reading the scripts?

If the convenience-versus-reliability argument doesn’t fully convince you to read scripts before running them, the security argument should, and we referenced xz Utils earlier.

In March 2024, the open source community just about avoided a catastrophe. A developer going by “Jia Tan” had spent approximately three years building credibility as a contributor to xz Utils, one of the most widely deployed compression libraries in modern Linux distributions. They used social engineering tactics, including fake accounts that pressured the original maintainer with feature requests and bug complaints, to eventually gain commit access.

Once trusted, Jia Tan inserted a backdoor that enabled pre-authentication remote code execution via OpenSSH on affected systems, hidden as x86_64 object code embedded in binary test files. The malicious code was only inserted during the release build process using commands concealed in Autotools scripts. It was assigned CVE-2024-3094 with a CVSS score of 10, the maximum severity rating.

The backdoor was discovered, funnily enough, almost by accident. Andres Freund, a PostgreSQL developer at Microsoft, noticed that SSH logins were consuming abnormally high CPU resources and decided to investigate. By that point, the compromised versions had already been distributed in several Linux distributions, including Fedora, Debian testing, openSUSE, and Kali Linux.

The parallels to the Proxmox community scripts are uncomfortable. The xz Utils project was maintained by essentially one overworked person, much like many open source projects. The attack exploited the fundamental trust model of open source: make contributions over time, earn trust, then abuse it.

The Proxmox community scripts project has experienced its own trust challenges. The original creator, known as “tteck,” passed away, leaving the project to community volunteers. Since then, key maintainers have resigned, citing concerns about project direction and decision-making. A post on the Proxmox subreddit from a former maintainer raises a troubling question: who is reviewing the code that runs as root on your hypervisor?

In other words, if an attacker was willing to spend three years infiltrating a compression library, what’s stopping a less sophisticated but equally motivated attacker from contributing a seemingly helpful commit to a Proxmox helper script?

What you can feasibly do

Read the scripts and keep a local copy

None of this means you should stop using the Proxmox community scripts. They’re genuinely useful, and for most homelab users, they save enormous amounts of time. I include myself in that, as my first port of call is often the Proxmox Helper repository if I want to deploy a new service. With that said, you should treat them with the respect that root-level code execution on your hypervisor deserves.

Firstly, and most importantly, you should actually read the script before you execute it. Download it, open it in a text editor, and understand what it does. Don’t just skim the CT script either. Follow the chain: read build.func, core.func, and the install script too. Once you’ve read it once, you just need to keep an eye out for changes, as those stay largely the same. In the case of build.func and core.func, these are the most vital scripts to keep an eye on, as compromising those means compromising practically every script in the repository.

If you wanted to be extra safe, you could pull the repository at a specific commit hash that you’ve reviewed, and then use that as your base to invoke scripts going forward. This way, you know the code hasn’t changed since you last audited it. There’s even a ProxmoxVE Local repository aimed at enabling exactly that, complete with its own web UI.

You should also check for hardware compatibility. To be honest, this one isn’t as big of a deal as the security side of things. If you try to run it and it doesn’t work, you can work backwards to figure out what the problem is. However, especially if you have abnormal or older hardware, you shouldn’t assume that it’ll support your machine out of the box. Even in my case, with the 7900 XTX, I had to put in extra work to get it up and running.

The Proxmox Helper scripts are great

Just don’t rely on them

The Proxmox community scripts exist in an interesting space. As some in the community have noted, they’re comparable to the Arch User Repository: a curated but community-driven collection where the expectation is that users understand what they’re installing by looking through the PKGBUILDs first. The general wisdom from the AUR applies here too: if you don’t understand how a script works by reading its source code, don’t run it.

Personally, I’ll keep using these scripts. They make managing my Proxmox homelab dramatically easier, and the community behind them does genuinely good work. But every time I run one, I read it first. Every single time. To me, convenience is not worth handing root access to code you haven’t vetted, no matter how popular of a project it is.